So, Frankenstein. He’s the monster with the lightning bolts… no, wait. No. He wasn’t the monster. He’s the doctor?

Frankenstein is the story everyone knows—or do they? The image of the monster with lightning bolts in his neck is so ingrained in our collective consciousness that it springs to mind immediately. But asked to detail the plot, how many of us could actually do that?

Barry Moser, No Father Had Watched my Infant Days, wood engraving in a suite of prints accompanying Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus, West Hatfield, MA: Pennyroyal Press, 1983. The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Jeffrey P. Dwyer; PML 127245.6 © Pennyroyal Press.

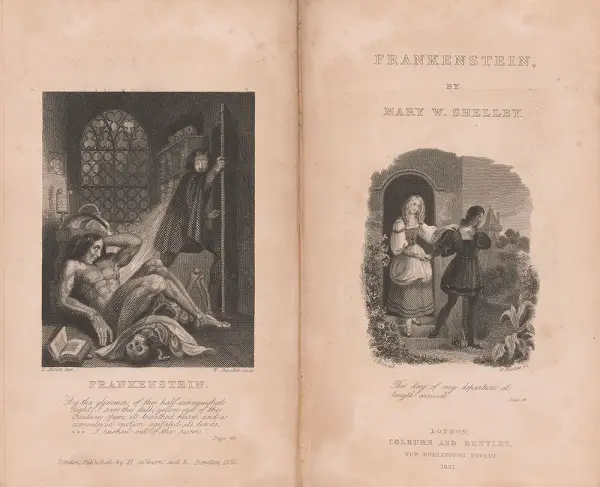

The story was first published 200 years ago, and has given rise to an enjoyable exhibition at the Morgan Library & Museum: “It’s Alive! Frankenstein at 200,” that pairs the academic and the Gothic; the backstory and the popular interpretations.

Mary Shelley's original 1816 book, entitled Frankenstein; or The Modern Prometheus, drew inspiration from both a love of the Gothic as well as the scientific discoveries made during the European enlightenment. The supernatural as portrayed in books and paintings—the spooky and the sublime, the ghosts and the graveyards—was popular fodder then, while scientific experimentation also thrived. Shelley was 18 when she started the novel. She came from an intellectual background, the daughter of feminist theorist Mary Wollestonecraft and the novelist and philosopher William Godwin.

Henry Fuseli (1741–1825), The Nightmare, 1781, oil on canvas. Detroit Institute of Arts, Founders Society Purchase with funds from Mr. and Mrs. Bert Smokler and Mr. and Mrs. Lawrence A. Fleischman /Bridgeman Images.

This love of the Gothic and the surreal is showcased in one of the most interesting artworks in the exhibit, a painting by artist Henry Fuseli entitled “The Nightmare” (1781). Considered the greatest horror painting of the 18thcentury, it shows a young woman swooning dramatically across her bed while nightmarish figures look on. Shelley would have been aware of this feverish painting, and it may well have influenced her writing of some of the final scenes in the novel. The painting itself is like a microcosm of the strong Gothic influence of the time.

Discussions of the scientific and the supernatural were popular topics of the day—the idea for the novel stemmed from a discussion between Shelley's husband (Poet Percy Shelley) and Lord Byron, who were talking about the idea of animating a corpse. From her own reading as well as the emphasis on these subjects in the current culture, Mary Shelley would have been aware of anatomical dissections, as well as electrical experiments on corpses.

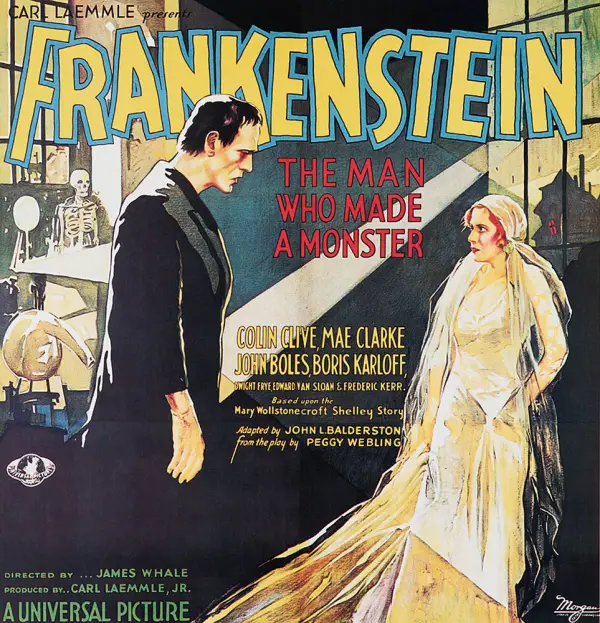

Carl Laemmle Presents Frankenstein: the Man who Made a Monster, lithograph poster, 1931. Collection of Stephen Fishler, comicconnect.com, Courtesy of Universal Studios Licensing LLC, © 1931 Univeral Pictures Company, Inc.

The first part of the exhibit first focuses on the academic, primarily manuscripts and books, and then leads us into the forays into popular culture. It’s in this second room that you’ll feel a sense of familiarity, because these are the images that populate our consciousness. We see film stills and comic books, sketches and photographs and posters, and even a wig and torso model. It’s in these often-garish, larger-than-life images that we see Boris Karloff as the Monster in the 1931 movie version, as well as images from Mel Brooks’ classic tongue-in-cheek film Young Frankenstein. The playbills are also particularly enjoyable—they’re materials that bring us into the time period, but they’re also familiar. Don’t miss the original 1931 screenplay, as well as some of the modern comics.

The transition to the gallery of modern interpretations may initially seem jarring, but we quickly realize that we’ve been well prepared by what’s come before. It’s also in this room that we realize that the story and its themes have endured not just because of these endless interpretations, but, as the exhibit reminds us, because of the universality and current relevance of the main ideas: the role of the outcast; scientific ethics and experimentation; violence against women and children. They’re themes that continue to affect us today.

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (1797–1851), Frankenstein, or, The Modern Prometheus, London: Henry Colburn and Richard Bentley, 1831. The Morgan Library & Museum; PML 58778.

And don’t miss another striking image early in the exhibit that you might well walk by. This one isn’t of the monster or of the doctor: it’s of Mary Shelley, who herself led a deeply tragic life. (Her husband and several of her children died young.) Here, a portrait of her somehow grounds the exhibition, making us remember that this was, in fact, a story written by a teenager; that it’s a story that continues to be read and analyzed, spoofed and discussed. It reminds us of the book’s continuing power, and why it is, in fact, still very much alive.

The Morgan Museum & Library is located at 225 Madison Ave. Call 212-685-0008 or visit themorgan.org for more information. It’s Alive! Frankenstein at 200 is up through January 27, 2019.